It’s Better to Burn Out Than Fade Away … Or Maybe It Isn’t

Bigfoot 200 in 2025 would be my 21st 200-mile race, and my 6th time running Bigfoot. It followed on the heels of my unsuccessful attempt at Tahoe 200 eight weeks earlier. I had gone into Tahoe feeling burnt-out and apathetic about both my training and the race itself. Although there were multiple factors that contributed to my DNF at Tahoe, my ambivalence toward the race had been at the center of it all.

Recognizing and acknowledging my feelings of being burnt-out was a strong first step, but it wasn’t a solution. A real solution would require more time. And time was something I didn’t have a lot of between Tahoe and Bigfoot. After a week of recovery from Tahoe, I jumped into a short, 5-week block of training for Bigfoot. I hit all of my key workouts during the training block, but, outside the context of those specific workouts, I was regularly allowing myself to shorten the lengths of the runs and to reduce the amount of climbing I was doing. Cutting a run short can be a smart decision when your body is not recovering adequately from previous training. But this wasn’t a case of responding to what my body was telling me, it was a case of not feeling like I wanted to train any more than was absolutely necessary. Ordinarily, I would have been excited to push hard in the workouts and to savor the easy days. And, as the race drew nearer, I would have been eager to get to that starting line so I could see if I was still capable of challenging my perceived limits. But I felt none of that. Instead, I felt mentally worn out.

Course Changes

Two days before the race, the race director sent a note to inform runners that local forest fires had caused a major re-route of four of the fourteen race segments, totaling more than 43 miles of course alterations. The modifications reduced the amount of technical trail, and eliminated quite a bit of climbing and descending. This left the course with more flat terrain and gently graded ascents than existed on the original course. While I can compete reasonably well with my fellow runners in tough climbs and descents, I find that the flatter terrain tends to favor the young and speedy runners. Nonetheless, I was still happy that the race staff had done the work to map a non-repeating route that was safe and was acceptable to the US Forest Service. This was a stark contrast to the 2024 race which had also been impacted by nearby fires. In that year, the gorgeous and challenging point-to-point Bigfoot course had been turned into four repeats of a 48-mile stretch of trail.

A Strong Start

A horn’s blast signaled the start of the race at the strike of noon, and everybody near the front of the lineup pressed forward on the strength of their fresh legs. I didn’t start slowly, but neither was I in a rush. I slipped into the pack somewhere around 20th place, preferring to maintain a manageable level of effort from the start.

I was moving well and feeling strong during the 12 miles from the Start to Blue Lake. The first several miles are a steady but mostly gentle ascent, followed by some mixed terrain. The section ends with almost five miles of runnable downs to the aid station. I moved efficiently along the rolling terrain, then picked up my pace for the long descent, passing several runners along the way. In the weeks leading up to the race, I had done a number of workouts specifically designed to ensure my quads were as resilient as I needed them to be. As a result of those workouts, I felt confident pushing myself a little harder on the downs throughout much of the race

My stop at Blue Lake aid station was on target, clocking in at 10 minutes to refill my bottles, re-stock my gels and get rid of any trash. Then I was back on the trail. The route from Blue Lake to Coldwater Lake was one of the sections affected by the wildfires. Specifically, the out-and-back to Windy Ridge aid station had been cut, reducing the course distance by 8 miles and eliminating 1700 feet of elevation gain.

I typically run the early part of 200s conservatively. This year at Bigfoot I pushed a little harder than I normally do when coming out of Blue Lake. That extra effort was driven by two concerns. First was my belief that the course modifications were going to make this year’s race considerably faster than all previous years (except 2024) and if I didn’t take advantage of the course modifications I would be giving away time. The second concern was that, with this year’s deeper field of fast competitors, there would be less opportunity to move up in the field during the later stages of the race. It is up for debate whether I should have let those concerns impact how I ran my race, but when I was in the moment running through those early portions of the course, the reality is that I let them affect me.

Pushing

It wasn’t long before I caught up to a trio of runners, two of whom would dominate much of the race, Killian Korth and Brody Chisolm. I stuck with them until we all stopped to fill up at what I believed to be the last source of water for the next 9 or 10 miles. They chugged some water, filled up a bottle each and then got moving. I needed more water than they did, so I took the time to drink at the stream and then to fill up three additional bottles. By the time I climbed back up to the gravel road on which we had been running, they were around a bend and out of sight.

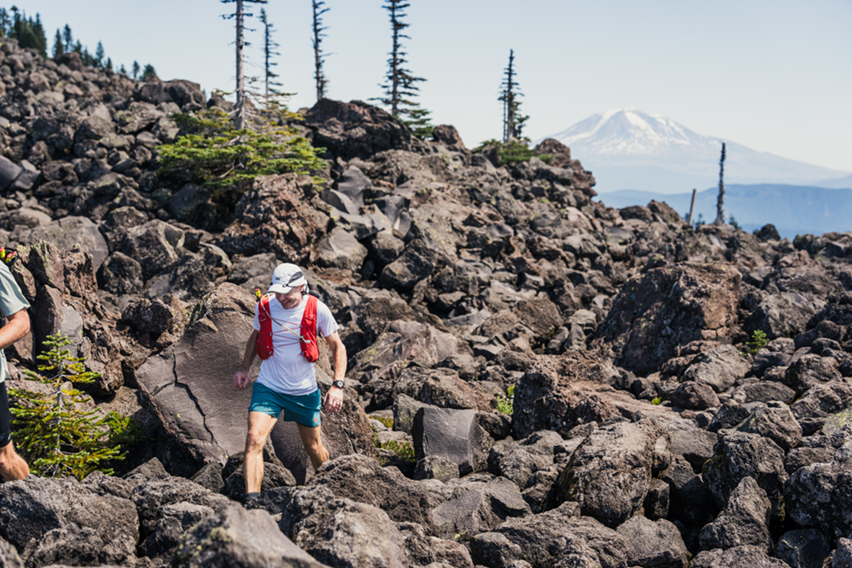

Whatever lead Killian and Brody had on me from the stop at the stream, I compounded by missing the turn from the road onto the singletrack toward Johnston Ridge. I followed the road a quarter-mile past the turn before realizing my mistake. Once I was back on the trail, my still-fresh legs carried me easily up the ascent. After hitting the top of the climb, it was essentially a long, flowing downhill most of the way to Coldwater Lake. That descent felt great this year, and I rolled into Coldwater Lake aid station at mile 37 in 5th place.

Coldwater Lake to Elk Pass

The climb from the northeast end of Coldwater Lake to Mt. Margaret went by quickly. I was moving well, and I have always enjoyed the relentless ascent of that section. The course ascends almost 5000 feet in 8 miles, and that kind of climb is right up my alley. I just focus on the trail and push at a strong, steady effort. No stopping, no breaks, keeping the critical items in my pack accessible so I don’t have to slow down to pull something from the rear pouch. I didn’t have poles for this climb, which meant my legs would be taxed more than usual, but I hoped the payout would be that my triceps and shoulders would be better rested for pushing hard with the trekking poles later in the race. As it turned out, I tied my previous fastest ascent from Coldwater to Mt. Margaret, which would indicate the lack of poles didn’t hurt me in any way for this climb, although I might have paid for it later during the ascent to Quartz Ridge.

From Mt. Margaret, it was a fun descent to Norway Pass aid station in the darkness. Heather helped me keep my stop at Norway Pass efficient. Then it was eleven relatively easy miles from Norway Pass to Elk Pass.

The Old Guy

I arrived at Elk Pass in 6th place feeling strong. I had run faster than planned, so I actually beat Heather to the aid station, which is remarkable only because it has never happened before in all the times she has crewed me. I owe her a better prediction of my pace for this section next time.

The aid station crew was quick to bring my drop bag while I sat down in one of their chairs. As I began filling my hydration bladder, I noticed that a woman sitting nearby was watching me. The woman wasn’t wearing running clothes, so I knew she was either crewing for a runner or serving as a volunteer at the aid station. After a minute or two of observing me, and in a tone bordering on mild disgust, her only words to me were, “I can’t believe my friend isn’t beating you. She runs all the time.” The woman was apparently shocked that some frail, gray-haired old guy was ahead of her friend. I was entertained by the comment, so I just looked at the woman and gave her a shrug, as if to say “even though I have no idea who your friend is, I agree that it is absolutely inconceivable that your friend isn’t crushing a feeble old geezer such as myself.” Unimpressed, the woman returned to casually observing me and idly waiting for her runner friend. Departing the aid station a couple minutes later, I couldn’t help but smile at the encounter.

The 15-mile route From Elk Pass to Road 9327 was fun, and I hammered down the long descent to the aid station with confidence that my quads were still holding up nicely. Road 9327 was another quick stop with Heather’s help, and then I was off to Spencer Butte aid station, mile 93. Although the heat was building, the weather so far had been mild compared to some of the hotter years at Bigfoot. Coming out of Spencer Butte around 11 AM onto a short stretch of paved road, I was moving slowly, walking what could have been run. I was in 8th place at this point, and I knew I was taking it easy on myself, so I picked up the pace when I hit the descent to Lewis River. That section of trail is always overgrown, probably because not many casual hikers want to go up or down such a steep slope. As in previous years, it was difficult to see where my feet were going to land through the leaves and grass. That added a small element of risk to the descent, but I couldn’t resist pushing the limit anyway. I managed to pass a runner and slip into 7th place during the descent, but it would be a short-lived gain.

Slowing Down

The trail from Lewis River aid station to Quartz Ridge is a tough, relentless challenge. With 7300 feet of cumulative elevation gain, it is the biggest climb of the course, and the many short, steep descents along the river are more of a disruption than a respite. In retrospect, I am a little surprised that I was able to push so steadily for so long in the race despite the apathy that had colored my running for the past few months. Part of it, I suppose, was the simple discipline of setting a goal and doing what is necessary to achieve it. But the rest of it probably came from my refusal to let Bigfoot 200 become a repeat of Tahoe

I had kept my feelings of burnout at bay for the first 114 miles, but, not long after departing the Lewis River aid station, that wall began to crumble. My lack of emotional connection to the race started having an impact. Intellectually, I knew that the ascent to Quartz was one of the critical portions of the race for me. The massive ascent had typically been a great opportunity for me to take advantage of my climbing strength, but this year I couldn’t seem to tap into that strength as readily as in the past. The apathy wouldn’t let me.

It also didn’t help that I was feeling sleepy. I fought it for a while, but 8 miles into the section I decided to curl up alongside the trail in the hope that a nap would revive and re-energize me. I set an alarm on my phone, and then closed my eyes. A fog of semi-sleep immediately overcame me and served to reset my brain a little, but those 5 minutes didn’t have the intended effect of truly refreshing me. As I began the climb again, I was still moving slower than I knew I was capable of. The discipline of adhering to my nutrition plan ensured I had been consuming enough calories to provide the energy I needed, but my mind didn’t force my body to tap into that energy

Partway through the series of climbs, Harvey Lewis and Mike Greer blew past me on a descent that I was walking. The mere fact that I was actually walking on a downhill stretch of trail should have been enough to set off my internal alarms, but there I was…just walking. Harvey and Mike’s presence helped to temporarily pull me out of my lethargy as I sped up to follow in their wake, but external motivators are rarely enough to keep me moving through tough circumstances over the long haul. Eventually, I let Harvey and Mike slip away as I slowed down again. If there was any positive side to this encounter, it was that my choice to increase my intensity forced me to acknowledge that I should have already made that switch on my own. I shouldn’t have needed someone passing me as a motivator. I don’t think that acknowledgment made a lot of difference in the remaining miles to Quartz Ridge aid station, but it would make a difference 55 miles later in the race.

The Easier Sections

Clocking in at 28 minutes, Quartz Ridge was my second longest aid station stop of the race. Only Chain of Lakes, where I slept for 90 minutes, was longer. Three specific activities caused the Quartz aid time to drag: a shoe change, a pack change, and eating food at the aid station rather than walking out of the aid station with the food in hand. The shoe swap at Quartz was the only time I changed shoes during the race, and it was necessitated by a slightly gritty feeling around my toes. For me, a change of shoes includes loosening my gaiters, taking off my shoes, wiping my feet with a damp rag, drying my feet, putting on clean socks, and then putting on the new shoes and getting the gaiters back into place. It’s not a lengthy process, but it does take a few minutes to do it right. The pack change was the result of Heather noticing my hydration pack had gotten a bit sweaty and realizing it might be a bad idea for me to go into the night with a damp pack. I had no specific reason that I recall for eating my food at the aid station rather than walking out with it, so I will speculate that it was simply another instance of being apathetic about my performance

Once I did get back on my feet, I moved slowly through a section that includes a lot of what should be fast downhills. As a result, my pace from Quartz Ridge to Chain of Lakes in 2025 was the slowest I had ever run that section in my six runs of Bigfoot. This was now the second consecutive section where I let the general feeling of burnout and apathy impact my willingness to push my body to its capacity.

I arrived at Chain of Lakes, mile 134, at 2:15 AM Sunday morning. This was my only planned stop for sleep during the race. Heather was ready for me and had already prepared a cot with an additional air mattress and one of our own blankets. I was asleep moments after laying down. Heather woke me up 90 minutes later. I had been in such a deep sleep that I was initially confused regarding what I was doing, and for several minutes I didn’t fully understand that I was participating in a race. Heather helped me get my gear back on, and she pointed me toward the course markers which would guide me to the next aid station at Cispus River. I started off at a walk before transitioning to a steady but slow run. It didn’t take long before the post-sleep fog cleared, and I regained the clarity of mind I needed. I didn’t know it at the time, but I had arrived at Chain of Lakes in 7th place, and had been passed by 4 runners while I slept, leaving me in 11th place overall

The next two sections of the course were brand new routes which had been created as a result of the wildfires. The first of those two sections started at Chain of Lakes. On the original course, runners would have gone from Chain of Lakes to Klickitat, a route that was almost entirely on singletrack, and included 3900 feet of vert along with some stretches of technical trail. The 2025 modified route went from Chain of Lakes to Cispus River, and was mostly a smooth dirt road with a total of only 1300 feet of vert. Leaving Cispus River aid station, the new route to Twin Sisters included some singletrack, but the majority of this section was another dirt road, this one gently graded for an easy climb. As with the previous section, the new route was significantly easier than the original route from Klickitat to Twin Sisters. In total, the changes to these two segments of the race eliminated about 1.5 miles and 3500 feet of vert

For both of the alternate sections, I just wasn’t pushing myself as I should have. I knew I was trying to perform well in the race, but that knowledge didn’t translate to me challenging myself as much as I was capable of. It was as if there was a gap between the intellectual portion of my brain and the emotional portion. The burnout I’d been feeling in my training for the past few months had fully reared its head. And by the time I reached Twin Sisters, it had been four consecutive sections in which I underperformed. My slow ascent of the dirt road to Twin Sisters led to another issue: monotony, which, coupled with sleep deprivation, grew into sleepiness. I ended up laying down three or four times on the side of the road to get some sleep. Each attempt was about five minutes long, and only during my last attempt did I actually sleep for a couple minutes. By the time I reached Twin Sisters, mile 170, I had dropped back to 15th place, which was not surprising considering how I’d been moving.

The Finish

Harvey Lewis was at Twin Sisters aid station when I arrived. He departed a few minutes later. I was relatively efficient at the aid station, although I did take a few minutes to chat with volunteers Helgi Olafson and Wes Plate, both of whom I knew from previous races and both of whom have extensive 200-mile race experience. By the time I left Twin Sisters, I had regained some level of excitement for the race. And, from my experience chasing Harvey and Mike on the way to Quartz Ridge, I knew I had it in me to flip that switch and push myself hard. I passed Harvey not long after the aid station, which put me in 14th place with 28 miles to go until the finish. My knees were bothering me by this point, slowing me on the short, punchy ups and downs. I attributed the pain to the fact that I had been a bit less disciplined than normal in my consumption of tart cherry juice in the weeks leading up to the race. Tart cherry juice has always worked miracles on any kind of inflammation I might otherwise experience as long as I drink it daily

The last few miles to the final aid station at Owen’s Creek are known as the Green Tunnel because of the lush, overhanging trees and the thick overgrowth that typically blankets the area. But the trail was easier to follow and less overgrown than in any of my previous races at Bigfoot. For that, I thank the dry weather leading into this year’s race, and I thank the 2024 Bigfooters for trampling down the overgrowth on their 4 trips through the green tunnel during last year’s fire-modified course

My pace for the 18 miles from Twin Sisters to Owen’s Creek ended up being my fastest time ever through this section by more than a minute per mile. Some of that speed was likely a result of underperforming in the earlier sections, but I’d like to believe that the other contributor to that speed was my choice to tap into the internal strength that I had relied on in past races.

Heather greeted me as I entered Owen’s Creek aid station, and she quickly helped me get what I needed before sending me on my way. I had been told the 13th place runner was well ahead of me, and I was relatively certain I had a solid gap on the 15th place runner, so I didn’t see a lot of reason to continue my hard push. Instead, I decided to relax and make these last 11 miles an easy walk-jog to the finish. While that made for a leisurely final section, I took it so slowly that I actually set a PR for my slowest “run” to the finish. I was, in fact, 6 minutes per mile slower than my previous slowest finishing section at Bigfoot. Hey, it’s still a record, right? 🙂

I picked up the pace a little when I hit the high school track in Randle, crossing the finish line in 14th place in 61 hours, 46 minutes.

Despite my mental and emotional struggles during the 69 miles from Lewis River to Twin Sisters, I was happy with my experience in the race, and I was happy with how I’d performed overall. In particular, I felt that my planning of calories, fluids and electrolytes had been spot-on. And, even more importantly, my execution of that plan was as close to flawless as I have ever achieved in a 200-mile race. If there was one element of the race that kept my burnt-out mindset from completely torpedoing my race, it was my execution of that nutrition plan. The brain aways does better and stays more positive when it has fuel.

In the weeks since the race, I have decided that, in order to escape the burnout that has plagued me these last several months, I am going to take an extended hiatus from the high volume of training I have been doing for these last eleven years. I am going to take a long off-season in which I simply maintain a low-level base of running without the constraints of a specific running regimen. I’ll supplement my running with hiking and adventuring, but the key is that I want it to be fun and energizing and not excessively taxing on my body and mind. I have canceled my race at Moab 240 this year, and I have canceled my race at Tahoe 200 in June of next year. Sometime next year, maybe in February or March, I will begin ramping up my training volume and intensity. It is my hope that I will return to Bigfoot in August of 2026 with the level of excitement and energy that I have typically brought to my races. And if that goes well, maybe I will also see some of you on the starting line of Moab 240 in 2026, two months after Bigfoot.

Key Takeaways From The Race

- My nutrition and hydration were spot-on. I had energy available in my system throughout the race, and I didn’t feel any ill effects from the heat. There were no lows that were driven by lack of energy, fluids or electrolytes. My depth of knowledge in this area has grown over the years, and my ability to accurately plan what is needed has grown as well. It’s hard to overstate how much difference this has made in my racing.

- My lack of trekking poles from the start through Norway actually sped me up during the ascent to Mt. Margaret as well as in the earlier portions of the course. However, I still suspect some of my climbing later in the race might have been negatively impacted by leg muscles which were likely more tired than they would have been if I had used poles earlier. Either way, I will want to consider even more closely than in the past which sections are best suited for poles in any given race.

- I didn’t discuss this in the narrative above, but planning my calorie and fluid consumption around the water-to-water distances worked very well. It gave me manageable, bite-sized portions of time to focus on specific nutrition targets rather than just having one big goal for the aid station-to-aid station distances. The detailed planning for this was onerous, but it was worth the effort for someone like me who enjoys planning.

- I was happy throughout the race that I had taken the approach of carrying less fluids and then filling up in the streams at almost every opportunity. There was a time cost for each of these water stops, but the physical and psychological benefits of having less weight in my pack outweighed the lost time, in my opinion. In some of my past races at Bigfoot I used the “carry more water and have a heavier pack” tactic, and in some of the races I used the “stop for water frequently but have a lighter pack” tactic, but I was never able to decide which approach was better for me. I think I’ve finally decided: less fluids in the pack and more frequent water stops is the winner.

- My aid station stops at Bigfoot were more disciplined than they had been at Tahoe 200 earlier this year. At Tahoe, I felt a little frazzled, particularly at the first aid station, and I allowed distractions to interfere with my efficiency. Prior to Bigfoot, I took the time to document the sequence in which I wanted to complete my aid station tasks, and I largely followed that sequence throughout the race. I did have a couple slow aid station stops at Bigfoot, but they were the exception.

- My lack of emotional engagement negatively impacted my performance at both Tahoe and Bigfoot. I must emotionally re-engage with my races and my training. I truly wanted to push hard at Bigfoot, and I did it successfully for a while, but when things got tough it was difficult to find the fire in me. I have to get the fire back. Canceling two major races and scheduling a break from regimented training for the next several months are intended to help me re-light that fire. Even back when I considered myself a road runner, I loved looking up into the mountains, spotting a huge rock outcropping, and then hiking the shortest, steepest route possible to those rocks, preferably without any kind of trail. Just grinding up the mountainside step after painful step. I loved it! In the time between the end of Bigfoot and the writing of this race report, I have already done several of those wonderfully tough and fun hikes. Rediscovering the roots of my love for trail running has already brought an element of joy back into my outdoor endeavors. In the coming months I hope to keep finding those sparks that will eventually explode into a fire.