The Race

Tahoe 200 and I have had a tumultuous relationship that began in 2016 when it was the second 200-miler I had ever run. My results the first four times I ran it consisted of a 4th place finish, a 6th place finish and two DNFs – Did Not Finish. One of the DNFs was for medical reasons, and the other was because I couldn’t get my mind to fully engage in the race I was supposed to be running. 2023 would be the fifth time I ran Tahoe.

The Route

The specific route we would follow for Tahoe 200 would be a bit different than previous years, although its length of 206 miles would be approximately the same. The traditional route was a 205-mile non-repeating loop around the entirety of Lake Tahoe. This year, the route would utilize 103 miles of the same trail, but it repeated those 103 miles rather than utilizing the additional 102 miles of trail on the west side of the lake. The damage from the Caldor fire a couple years earlier was still being repaired, so the trails through that area were not available for athletic events, preventing a complete loop of the lake.

The 2023 course essentially consisted of two out-and-backs. The runners started the race at Heavenly Ski Resort in the middle of the course, and then traveled south 31 miles to a turnaround point at Housewife Hill. From Housewife Hill, participants ran north for 103 miles, passing through Heavenly on the way to the northern turnaround at Ward Creek. From Ward Creek, participants returned 72 miles south to finish back at Heavenly.

Start at Heavenly to Armstrong Pass

At 9 AM on Friday, July 24, Tahoe 200 began with a short dash up the Heavenly Ski Resort parking lot to the singletrack trail we would follow 31 miles south to our first turnaround at Housewife Hill. I moved fast enough to be among the people who were generally out front, but I had no interest in forcing my way to the actual front against runners who were obviously motivated to seize a top position early.

Over the course of the first few miles, I worked my way through most of the people who had started out fast, and then found myself trailing directly behind Michele Graglia. Michele was an Italian runner who had won Moab 240 in 2020, and was one of the people I considered to be a top competitor at Tahoe.

We’d been running for a little while in close proximity to one another when Michele called back to me, “One of the guys out front is running like he’s doing a speed workout.”

“That usually works well for about forty miles,” I joked. “And then you realize you’ve got another 160 miles to go.”

Michele laughed, and we continued our steady progress.

The first section of the course was a lot of fun. The trail was very runnable, the temperature hadn’t yet risen enough to affect me, and it felt good to finally be running a race I’d been looking forward to for quite a while. I kept a strong pace, but, eventually, Michele pulled farther ahead of me. I didn’t pursue him. It was too early in the race to be chasing anyone.

Armstrong Pass to Housewife Hill

The first aid station was Armstrong Pass at mile 14. I arrived feeling a bit disorganized. I had forgotten to read my aid station notes in the miles prior to the Armstrong descent, so I had to quickly read the notes while swapping bottles and grabbing some calories. It was a trivial indiscipline that cost me no more than a couple minutes, but I was a little disappointed with my poor showing, and I committed myself to not slipping up the same way again.

After a 4-mile ascent out of Armstrong Pass aid station, the trail began a long descent that would lead to Housewife Hill. While much of the trail was partially canopied by trees, the heat was inescapable. The day had started warm, and it was only getting hotter.

Five miles after Armstrong, I started feeling mild nausea from overexertion in the high temperatures. In an attempt to stifle the rising sickness, I sat down in the shade of a tree to drink some water. Before I’d even taken a sip, my gut wrenched in three strong heaves of watery vomit, emptying my stomach.

I rinsed out my mouth and got back on my feet, already feeling better. I came upon a stream almost immediately. I used the stream as an opportunity to drink some nice, icy water and to take some salt capsules. It was critical that I replace the fluids I had just expelled, and that I keep a proportional amount of electrolytes going in.

Housewife Hill to Armstrong Pass

Unlike my stop at Armstrong Pass, I made a point of taking the time to read my plan in advance of the mile 31 aid station at Housewife Hill. The plan looked good aside from one aspect. It called for me to keep this stop to 5 minutes. Although I was feeling reasonably well, the vomiting incident told me that I was still teetering on the brink of bigger, heat-related issues. Adhering to my 5-minute goal would not be a wise decision. All my race plans are built to provide a common starting point for me and for Heather, my sole crew member. We both understand that I must run by feel, and therefore we must always adapt the plan to reflect the reality of the moment. And the reality of this moment was that I needed to absorb more fluids and more electrolytes before I pushed myself farther.

I didn’t extend my stop more than a few minutes, but it provided adequate time to sit down in the shade of the aid station canopy, to drink a couple cups of cold Coke, and to take a 1000mg tablet of sodium. It was enough, and it was necessary. I thanked the volunteers who had helped me, and I got back on the trail.

After Housewife Hill, the course backtracked 31 miles north to Heavenly. This meant every runner would pass the runners behind them, all of whom were still running south. Although it’s not always convenient navigating around oncoming runners on tight, singletrack trails, I do enjoy saying hi to friends and fellow runners I might not otherwise see during the race.

My focus on fluids and electrolytes at the aid station paid off, and, as I ran north, I was feeling good and moving well despite the afternoon heat. When I left Housewife Hill, I’d been in 6th place. By the time I hit Armstrong Pass at mile 47, I had moved up to 4th place.

Armstrong Pass to Heavenly to Spooner Summit

Armstrong Pass was a brief stop for me. I swapped empty bottles for full ones, got help filling my hydration bladder from the volunteers, and was on my way. The cooler temperatures helped me move even better, and within the first three or four miles of the section, during the ascent to Freel Pass, I moved into third place.

I arrived at Heavenly aid station at 1 AM. This would be my first opportunity to see Heather since the start line. My plan was to sleep for an hour at Heavenly to mitigate the effects of the paltry 3 hours I had slept the night before the race. Unfortunately, poor sleep before 200-milers had become so normal for me that my primary plan for races now included the assumption that I would go into the race already sleep deprived.

Typically, when a 200-mile race is preceded by a night with little sleep, there is a high probability I will end up practically sleepwalking through much of the second night of the race. I have often tried to minimize the sleepwalking by taking a couple five or ten-minute dirt naps alongside the trail. Sometimes that has worked, and sometimes it hasn’t. This year I was going to try to replace the dirt naps with a full hour of sleep in the comfort of a cot at an aid station the first night of the race. And that meant it needed to happen at Heavenly.

The runner I had passed on the way back from Armstrong Pass, Jacob Rydman, arrived at Heavenly as I was finishing eating. I made my way to a sleep tent anyway. I was determined to make my sleep plan work. Besides, although I always found it fun to keep track of my position throughout the race, as far as I was concerned the real race hadn’t even started yet. All we were doing at this point was separating the front of the pack from the rest of the pack. Gaining or losing a few positions this early was somewhat irrelevant. If my past experience was any indicator, it would not be until somewhere around mile 110 or 130 that the race among the front of the pack would begin in earnest.

I took off my shoes, pulled some blankets over me, and then…nothing. I lay there without sleeping. I gave it somewhere between five and ten minutes before deciding sleep was not going to come. In the meantime, Jacob had done whatever he needed to do at the aid station and was already moving back up the hill away from Heavenly.

It took me another ten minutes to get my shoes back on, eat a few more bites of food, and then, trekking poles in hand, begin ascending out of Heavenly. I ended up passing Jacob about an hour-and-a-half into the section. I incorrectly assumed this meant I was back in third place. Unbeknownst to me, Michele Graglia, the race leader, had succumbed to ongoing heat-related issues and had turned around to drop out of the race. That drop meant I was actually in second place.

The heat on the first day had been devastating to many more runners than just Michele, and was a major contributor to 2023 having the worst overall finish rate of any year in Tahoe 200 history. I have traditionally suffered in the heat. It really walloped me two of the times I’d run the Moab 240, causing me to fall far short of my goals in races for which I had otherwise prepared well. I’d learned from those struggles, and had improved my pre-race heat acclimation considerably. While not perfect, my current pre-race protocol seemed to be keeping me moving well and feeling well. And that’s about all I could ask of it.

With Michele out of the race, Claire Bannwarth, a 34-year-old professional runner from France, was now the race leader. Claire had finished as fifth female in the highly-competitive Hardrock 100 only one week earlier. With less than a week to recover from a race known for its high elevation and serious climbing, the fact that she was leading at Tahoe was amazing.

The route from Heavenly to Spooner Summit consisted mostly of a gradual, 8-mile ascent followed by a fun descent to the aid station which was nestled into a grove of trees near a local highway. I moved reasonably well through this section, popping a caffeine tablet regularly to help me stay alert through the hours of darkness. I arrived at the aid station at 6 AM, confident the morning sun was going to help refresh my mental energy even further.

Spooner Summit to Village Green to Brockway Summit

Unfortunately for me, my arrival at Spooner Summit initiated a trend that would plague me at several of the remaining aid stations: consuming unnecessary time. On four of those occasions, I wasted time because I made extended, fruitless efforts to sleep. But at Spooner Summit, as at two of the other remaining aid stations, I was just a bit slower than I should have been, taking too much time swapping bottles, taking too much time eating, taking too much time getting my pack ready. It was time I could not afford to waste.

I moved quickly between Spooner Summit and Village Green, energized by the sun and by temperatures that had not yet risen as much as they soon would. At mile 98, Village Green was just a few miles short of the midpoint of the 206-mile course. It was there I learned that I had moved into first place. Claire had gone off course for 2 ½ hours during the previous section, and I’d passed her during the time she was getting back on track.

I spent exactly an hour at Village Green, a bit of that time attempting in vain to sleep on a cot by the stream at the back of the aid station. My attempt to sleep was unproductive. When I eventually realized I was not going to fall asleep, I got up, ate a little more, and then finally got moving again. Claire arrived at Village Green an hour after I had left, but, unlike me, she spent only 10 minutes at the aid station.

The route from Village Green starts with an easy run on a paved sidewalk through Incline Village, and then gets significantly tougher with the 1500-foot powerline climb to Incline Overlook. Saturday was another hot day. Making it even worse, during my entire powerline ascent the sun was positioned perfectly to blast me with heat. Like everyone else, I just pushed through it until the summit eventually arrived. After the big ascent there was still some climbing to be done, but at that point the climbing is broken up into manageable pieces and the rest of the route makes for relatively fast running to Brockway Summit.

Brockway Summit to Tahoe City

Heather was waiting at Brockway Summit for me. She helped to keep my stop somewhat efficient, although the slow rate at which I was nibbling on food stretched my time here longer than necessary. I departed the aid station just after 4 PM. I didn’t know it at the time, but despite my longer stay in the aid station, I had maintained the same lead on Claire. She arrived at Brockway Summit exactly one hour after I left.

This section was an easier one with a lot of descending. There were steeper ascents that I hiked, of course, but there was also a nice stretch of smooth, gentle, uphill trail where it was possible to do an extended uphill run. Before the descent to Tahoe City there is a rough section of trail with awkward footing and layers of loose, slate-like rocks. This portion of the trail always slows me down more than I want it to, but, as a whole, the section went well for me physically and mentally. I was alert and focused, and, before I knew it, I was being escorted into the Tahoe City aid station by my friend Cesare Rotundo, who was captaining the aid station and who has run numerous successful 200-mile races.

Tahoe City to Ward Creek and Back to Tahoe City

I arrived at Tahoe City, mile 130, just before 9:30 PM, and I was happy to see Heather again so soon. I told her I needed to sleep prior to getting deeper into the second night or risk a long session of sleepwalking. With the aid station positioned in the heart of Tahoe City, we felt having some “white noise” from the generator might be better than the intermittent noise from all of the passing cars. While the volunteers got some pancakes ready for me, Heather moved a cot into place. After I ate, I laid down. Unfortunately, the generator was just too loud. Eventually, we shifted the cot to a couple different spots, but couldn’t find a place that was quiet enough despite the earplugs I was using. In the end, I burned 90 minutes at the aid station without ever sleeping. Had my mind been a little less drowsy, I would have given up trying to sleep after five or ten minutes near the generator.

Claire arrived at Tahoe City at 10:40 PM, an hour and ten minutes behind me. It was around that same time I was finally giving up on my attempts to sleep. She spent fifteen minutes at the aid station and then departed a few minutes before me. And with that, I had dropped back into second place.

I caught up to Claire 4 miles later at the Ward Creek turnaround. As we started the return to Tahoe City, I took position about thirty feet behind her. Ascending out of the Ward Creek drainage, she moved strong and steady, choosing a slow-paced running movement on the steeper parts of the ascent while I chose a fast, hiking pace for the steeper portions. We both ran the flats and the gentler hills. With only 4 miles from the turnaround back to Tahoe City, it wasn’t long before were at the Tahoe City aid station once again.

Tahoe City to Brockway Summit

Claire maintained her aid station discipline at Tahoe City, refueling and resupplying in fifteen minutes. I changed my shoes and socks, and took the opportunity to refuel with some food and Coke. I also decided to lay on a cot for another ten minutes. I knew I wouldn’t fall asleep, but I hoped it would reset my mind to a more alert state. This shouldn’t have been a long stop, but everything seemed to take longer than it should have. In all, it was 40 minutes from my arrival to my departure.

Looking back at the race, the second stop at Tahoe City was much more critical than either Claire or I probably realized. From my perspective, Claire’s efficiency at that station essentially threw down a challenge that either I would accept or not. I could mimic her efficient stop at Tahoe City, and at the stops still to come, or I could fail to accept that challenge. Whether it was a conscious decision or not, I gave Claire a gift of 25 minutes by lingering past her departure from Tahoe City. My running pace from Tahoe City to the finish would end up being fractionally faster than hers, but I continued to give her free minutes at aid stations for the remainder of the race.

A mile outside of Tahoe City, at the start of the long ascent to the cliffs above the Truckee River Basin, I encountered Trevor Medding as he descended toward the aid station. I had identified him as a potentially serious competitor prior to the race, so seeing he was the next runner behind me didn’t provide me with a lot of comfort. Granted, he was ten miles and two aid station stops behind me, so it wasn’t as if he was nipping at my heels, but a lot could happen in the last 67 miles of the race, and if I didn’t sustain my effort level, I would be opening a door for him to catch me.

Sometime during the ascent from Tahoe City, I concluded that my aggressive climbing of the hills was keeping me awake much better than I had expected, particularly when coupled with the caffeine I was taking regularly. I was most vulnerable to feeling drowsy when I was hiking (as opposed to running) so I would continue this practice through the remainder of the race. This would obviously help me move faster as well, but my primary intent was to keep myself alert. If I could stay focused and alert, I would move faster regardless of the terrain.

Brockway Summit to Village Green to Spooner Summit

I arrived at Brockway Summit a few minutes after Claire departed, but again lost time at the aid station when I decided I needed to close my eyes in a sleep tent for twenty minutes.

This portion of the course went well for me aside from the climb up Tunnel Creek Road, which is shortly after Village Green aid station. The road itself lacks any overhead tree cover, and consists of white sand that seems to reflect every bit of heat from the sun. I was ascending the road during a hot time of day. My normal approach on long climbs is simple: never stop moving. The only exceptions I allow are if I need to do something critical like swapping bottles from the back of my pack to the front. However, during what should have just been a steady, 4-mile ascent to the Tahoe Rim trailhead, I stopped once during the climb, and again at the top of the climb. Both times, I’d felt as if the sun was baking me alive, and I was seriously concerned about overexerting myself and becoming a casualty of heat exhaustion. I don’t know if my two stops were entirely necessary, but I do know I didn’t suffer heat exhaustion, and that’s good enough for me.

Spooner to Finish at Heavenly

When I hit Spooner Summit aid station, mile 188 and the last aid station before the finish, I spent a few minutes laying down on a cot to see if I could snap my slightly foggy brain back to alertness. At this point, I correctly assumed Claire was too far ahead to catch, and I knew the runners behind me were too far behind to overtake me.

The final section was a slow one for me, and lasted from 7:15 PM to 1:15 AM. It took me six hours to go 18 miles. It was during the later hours of these final miles that the cumulative effect of only 3 hours of sleep the night before the race, and only 20 minutes of sleep during the race, really caught up with me. Neither caffeine nor focusing on intensity helped.

Confusion and uncertainty began to dominate my exhausted mind. First, without ever thoroughly checking my pack, I concluded that I was only carrying a headlamp rather than the headlamp and flashlight combination that I always carried at night. With my poor night vision, having only one light source was a detriment to moving swiftly on the descents. Second, I was firmly convinced that my headlamp batteries and the backup batteries were burning out more quickly than normal, and I thought they might not last all the way to the finish. Finally, I kept thinking I might be on the wrong trail even though I was seeing occasional course flagging. I thought the flagging looked old and worn, and I was afraid it had been inadvertently left from a previous Tahoe 200 where the runners might have followed a different route through this portion of the course. As a result, in addition to moving slowly, I must have stopped at least fifteen times to check the GPX course on my phone to verify that I was really on the correct trail.

Five or six miles from the finish, I found that I was back in cell phone range, so I called Heather to tell her my headlamp batteries were almost dead and I didn’t have a flashlight. I was worried I might need to drop out of the race because I was likely going to be lost and blind on some unknown trail in the middle of the night. In retrospect, it’s clear that all of these beliefs were laughably irrational, but, completely exhausted and sleep deprived at the time, my mind had slipped far down a very bad rabbit hole that I wouldn’t escape until I had a chance to lay down. Fortunately, Heather told me she knew she had packed a flashlight. I dug into my pack and, sure enough, there was the flashlight. Having the flashlight didn’t reduce my paranoia that I was on the wrong trail, but it did get me moving a little faster.

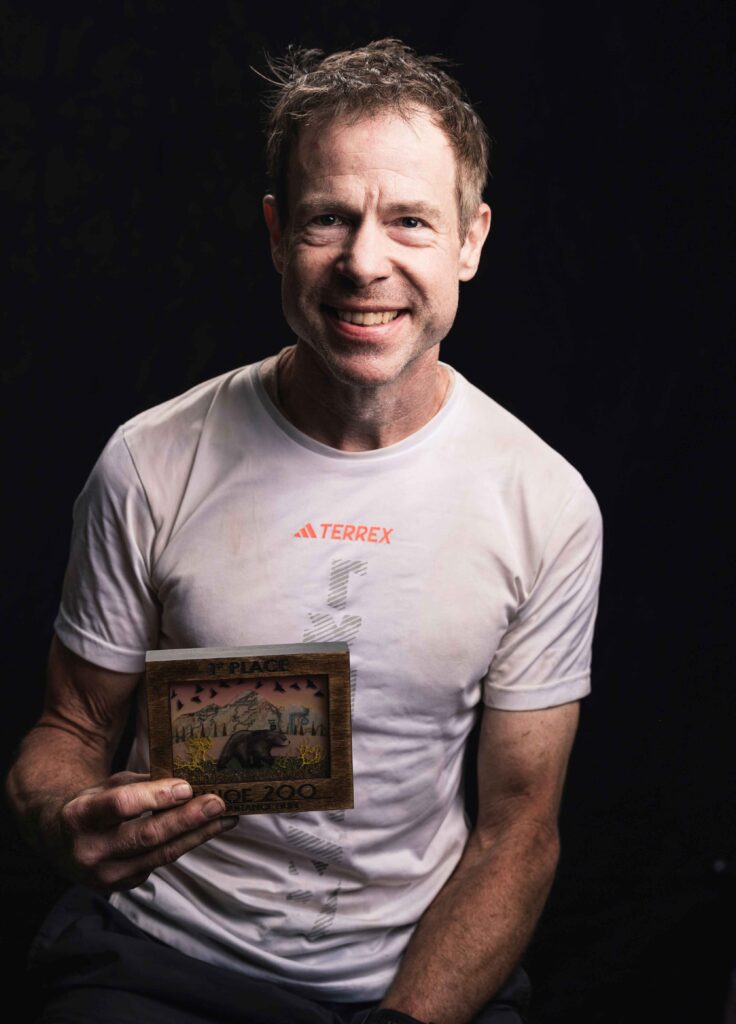

I finished Tahoe 200 in second place overall with a time of 64 hours, 15 minutes. Claire had finished 1 hour, 51 minutes ahead of me.

Claire had arrived at the Tahoe 200 start line less than a week after Hardrock 100, she overcame the deficit of going off course for 2 ½ hours, and she managed her aid station stops well while I spent a total of several hours longer than she did at the aid stations. To state it succinctly, she ran a better race than I did.

Epilogue

I couldn’t be much happier about my experience at the race and about my finish. When I criticize myself for things like wasting time at an aid station or making a poor decision during a race, I don’t do it to beat myself up or to stew in my misery. Neither do I try to hold myself to an impossible standard that can only lead to perceived failure and to a lack of joy. Instead, I examine my races closely in order to objectively analyze and understand what went well and what I could have done better. Only when I see myself and my actions with clarity can I find ways to improve my performance and to make my overall race experience even better. I still have much to learn and experience, and I hope to never lose the wonder in finding something else that improves my journey or hones what I’m already doing to an even sharper edge.

I am so appreciative of Heather’s support throughout the race, it’s difficult to express. She makes such a huge difference to my entire race. We are truly a team, each with our own roles and struggles. I try to return the support by crewing at her races, but I know that crewing a 100k (or the 100-miler she will be attempting next year!!!!) is significantly easier and less complex than the 200-milers she crews for me. Lately she has been setting some lofty race distance goals for herself, so I have a feeling that sometime soon I will have the opportunity to attempt to provide the same level of support to her at a 200-miler that she has provided at my 200s. She has set the crewing bar very high, and I can only hope to do it as well as she has.

Finally, and as always, thanks to the numerous volunteers and race staff who helped me along the way. I appreciate the tremendous assistance and encouragement you provided me on this very long journey.

See you on the trails!

Analysis. For those who are interested in a couple technical aspects of the race that I didn’t adequately address during the narrative, in the paragraphs below I’ll take a closer look at two specific topics – sleep and heat.

Sleep / Remaining Alert.

My attempts to sleep during the race were ineffective, and largely amounted to a waste of time. The amount of time lost was affected both by the number of times I attempted to sleep and the amount of time I spent laying down without sleeping during each of those attempts.

Ordinarily, I follow a self-imposed rule that I will never allow myself to remain laying down for more than five or ten minutes if I haven’t fallen asleep. Instead, I force myself to get up and get moving. Merely following that rule would have saved me an enormous amount of time in the aid stations, and would have been a game-changer. I don’t have a definitive explanation for why I allowed myself to deviate from my usual 5 to 10-minute limit, although I suspect it was related to just going into the race too fixated on the idea that my minimal sleep the night before the race meant I needed to get a solid hour of sleep sometime during the event. As the race progressed and my mind grew weary, it became difficult to dislodge that idea.

Compounding the loss of time was the fact that I tried at multiple aid stations to sleep rather than just once or twice. I should have done a better job of re-evaluating the situation earlier in the race, before I had become so sleepy that my critical thinking ability was dulled. If I had done that, I might have realized sooner that my strategy for staying alert was having enough of a positive effect that I just didn’t need the solid hour of sleep I’d planned. All of that is much easier said than done, but at least it gives me something to think about prior to my next race.

The first part of my strategy for staying alert was regular doses of caffeine. In the past, I’ve relied upon correctly assessing that I need some caffeine, and then remembering to take a tablet or two. I might go through six hours of darkness without taking a caffeine tablet, or I might take two tablets twenty minutes apart from one another. This unstructured approach was largely ineffective because it relied upon observation and action from a brain that had often become so sleepy that it could barely focus on the trail in front of me, let alone remember to take a pill with any regularity. So, at Tahoe I used a recurring alarm on my watch that alerted me every hour to take a caffeine tablet. I would turn on the alarm at night, and sometimes I would even leave it on during part of the day. This ensured I had a dose of caffeine going into my system at a regular cadence.

The second part of my alertness strategy was to make a conscious effort to sustain a higher intensity effort during periods when sleepiness was more likely. I know from experience that if I’m extremely sleep deprived, I am most likely to lose focus and essentially start sleepwalking anytime my pace slows to a walk. Typically, that means when I’m ascending a hill that is too steep or too technical to run. Of course, the threshold for “too steep to run” becomes lower and lower the farther I go in a race, which increases the opportunities for my brain to get foggy and for my hike to become a slow, sleepy trudge. The increased intensity had a secondary effect of speeding up my ascents, but mentally it was all about avoiding the foggy sleepwalk that is unrelentingly miserable whenever it occurs.

Heat.

Despite heat being one of the major challenges of this year’s race, it didn’t actually impact me as significantly as it has in the past. In the past, during the lead-up to races, I have typically focused on selecting hotter times of the day to do my training runs whenever possible. This approach fit my travel-heavy work schedule because most of the places I traveled were in hotter parts of the country. Regardless, that approach was still never as effective as I wanted it to be. Being retired now, my schedule has opened up considerably and has given me an opportunity to try different heat acclimation techniques. So, this year I switched to a daily sauna routine in the period leading up to my races. The mere fact that I could approach the acclimation in a daily, disciplined manner made a big difference in the effectiveness of the protocol.

The other action that had a positive impact on my ability to perform better in the heat was simply becoming more disciplined in consuming a well-balanced combination of fluids and electrolytes during the race. Sometimes I have succeeded at striking this balance, and sometimes I have failed. It went well for me at Tahoe this year, and I will do my best to continue that at my future races.

See you on the trails!

Wes Ritner

Photo credits are: Jason Peters, JP; Anastasia Wilde, AW; Heather Mitchell, HM; Anonymous but Wonderful Aid Station Volunteer, AWASV